The Case for Change

There are, essentially, two truths today about African agriculture: significant progress has been made, and there is potential for much more. Several figures point out the progress. Agricultural production has increased 160 percent over the past 30 years, far above the global average of 100 percent, although lagging South America (174 percent) and Asia (212 percent). Eighteen Sub-Saharan African countries have reached the Millennium Development Goal’s first target of halving the proportion of people who live in poverty. Country-level programs (the Ethiopian Agricultural Transformation Agency is one example), cross-border initiatives (such as the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme), and pan-African groups (such as the African Development Bank, the African Union, and the New Partnership for Africa’s Development) have all played important roles in these advances. Africa’s room for more growth remains vast, however. The continent remains a net importer of food, even though it has 60 percent of the world’s uncultivated arable land, and production has struggled to keep pace with a fast-growing population. To meet the needs of the 2 billion population expected in Africa in 2050, agriculture is the key. Agricultural transformation will build social cohesion, drive beneficial continental trade, provide a platform for sustainable exports to the rest of the world, and, most importantly, help create millions of jobs while pulling subsistence farmers out of poverty

What Has Hampered Africa’s Development?

Many factors have hampered Africa from reaching its full potential. As its population has doubled overall and tripled in urban areas in the past 30 years, agricultural production and food security have had to keep pace. Africa is the only continent where the absolute number of undernourished people has increased over the past 30 years. There are many reasons for the challenges, but three in particular stand out.

A multitude of (somewhat uncoordinated) initiatives. There are many great initiatives, with local and foreign funding, that aim to enhance the state of agriculture in Africa. However in many cases these programs are fairly uncoordinated, often have overlapping mandates, and, to a certain extent, compete against one another for funding and private investments. Pan-African coordination and focus is critical to the future.

Good ideas but not enough implementation. Forests have been harvested to produce the paper to document all of the strategies that have been developed. Through the years, countless commitments have been made and plans have been developed. Although progress has been made, now is the time for this to be all translated into concerted action.

Insufficiently developed ecosystems. The ecosystems required to develop a solid agricultural market in Africa are often underdeveloped in terms of political commitment, the quality of government, infrastructure availability, and regulatory frameworks, among other factors. There is a need for a true commitment among governments and stakeholders to put the basics in place to make these ecosystems happen.

Africa’s Agricultural Transformation at Three Levels

The value chain from farmer to market is central to any potential transformation of Africa’s agriculture. Transformation at three levels can bring broad benefits to this farmer-to-market value chain: Farmers. Smallholders contribute up to 80 percent of Sub-Saharan Africa’s food supply, according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, and Africa has an estimated 33 million smallholder farms, according to the International Finance Corporation. Increasing farmer capabilities would increase Africa’s output and, as a consequence, help solve Africa’s poverty and malnutrition crisis. Farmer-level transformation should seek to increase yields, reduce post-harvest losses, improve market access, and increase product margins. Transformation requires granular-level interventions that form the basis for sustained economic and societal success. Enablement in areas such as education, infrastructure, water management, and regulations is crucial as well. Public-private initiatives can ensure capability-building support and the development of structures in areas like financing. These initiatives are, by nature, very local. However, they can be facilitated from a pan-African perspective in three ways:

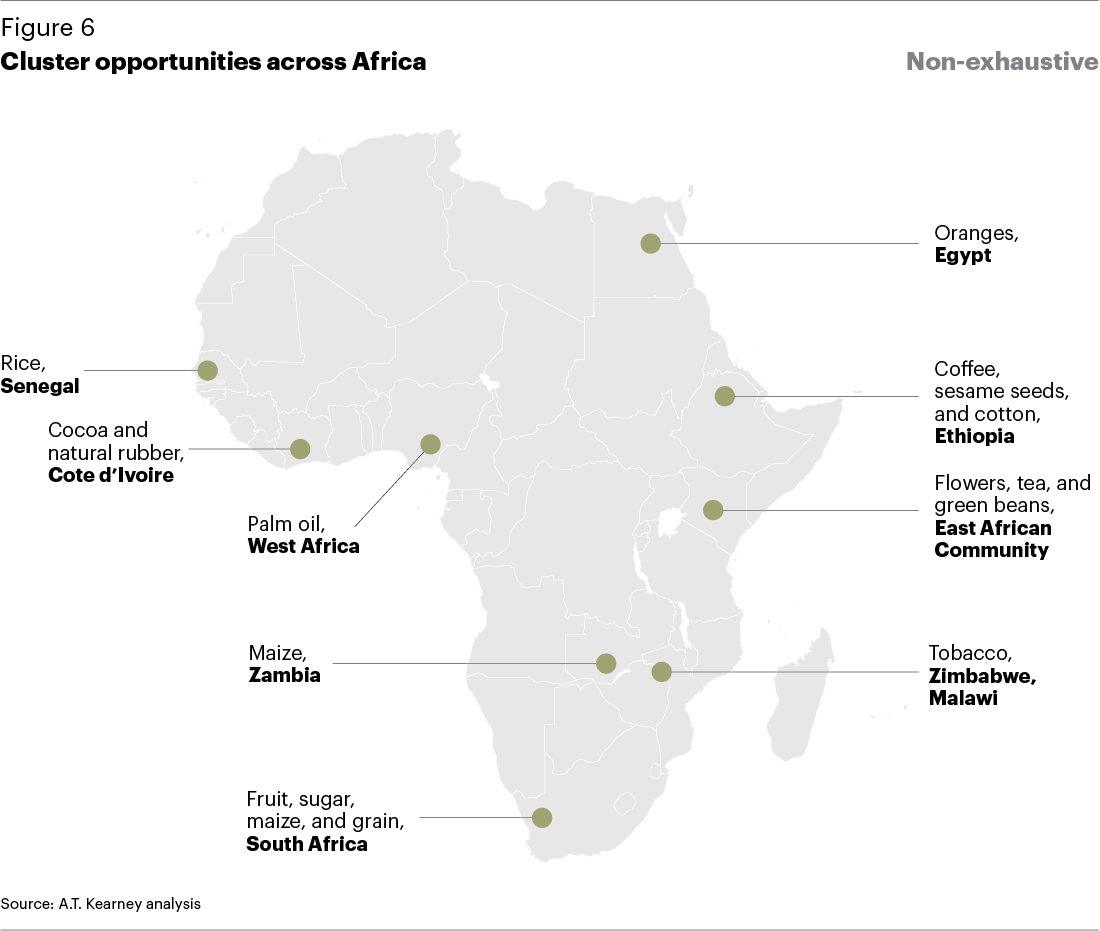

Clusters (macro). With agricultural ecosystems in place in this final, macro level of transformation, Africa can become a major agricultural player globally, facilitating the export of its products outside of Africa. Cluster-specific initiatives are typically based on product availability and production competence. Better supply, from farmers who have learned about and invested in improving their yields and product quality, helps build a stronger market. Dairy exports from New Zealand are one successful example of the development of a world-class ecosystem. Years ago, the New Zealand Dairy Board created a platform for best-practice sharing among its members to improve productivity and product quality and actively created export markets for excess products. Some of the Dairy Board’s activities became part of a new cooperative called Fonterra—now one of the leading global milk processors and dairy exporters, with roughly 22 billion liters of milk produced annually. Fonterra also produces more than 2 million tons of dairy ingredients, specialty ingredients, and consumer products annually—95 percent of which are exported. This allows New Zealand to punch above its weight in the global dairy market. Cluster-specific export initiatives like Fonterra should be a government goal in Africa. From a pan-African perspective, identifying sectors and coordinating initiatives across countries are essential steps to a transformation strategy.

Building Pan-African Ecosystems: Financing, Sustainability, and Government Enablement

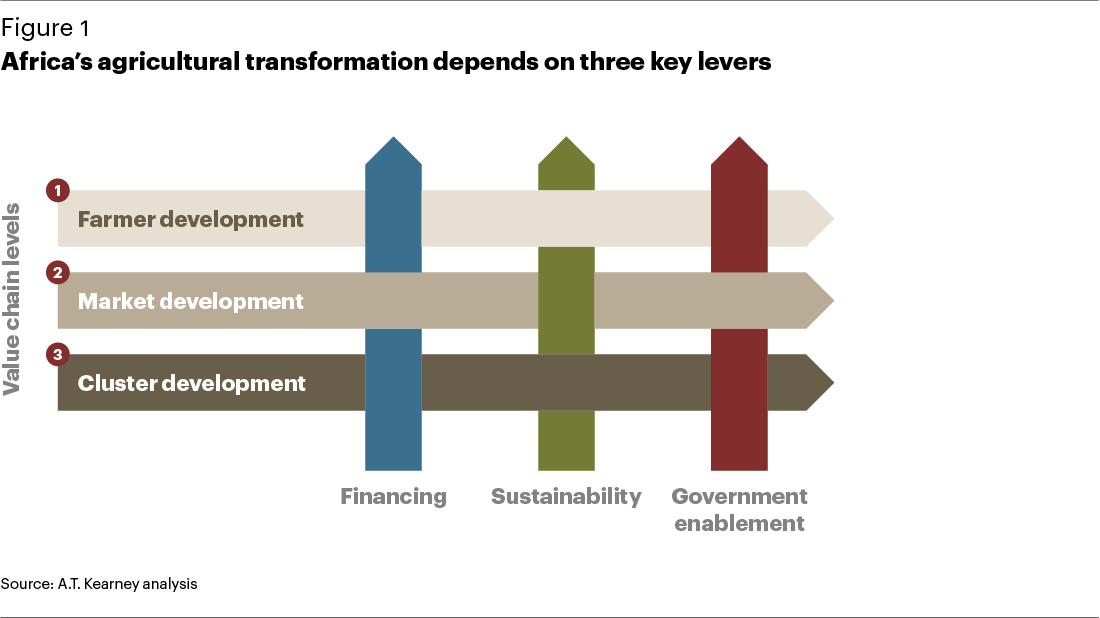

African smallholders do not yet benefit from best-in-class global farming practices. They are often trapped in a vicious cycle that prevents them from improving their productivity and income. These farmers are, however, the fabric of African rural societies. Their future success is crucial as Africa’s population grows and urbanizes. Strategies are only as effective as the change they bring about. Truly transforming African agriculture at the farmer, market, and cluster levels depends on three key levers: financing, government enablement, and sustainability (see figure 1).

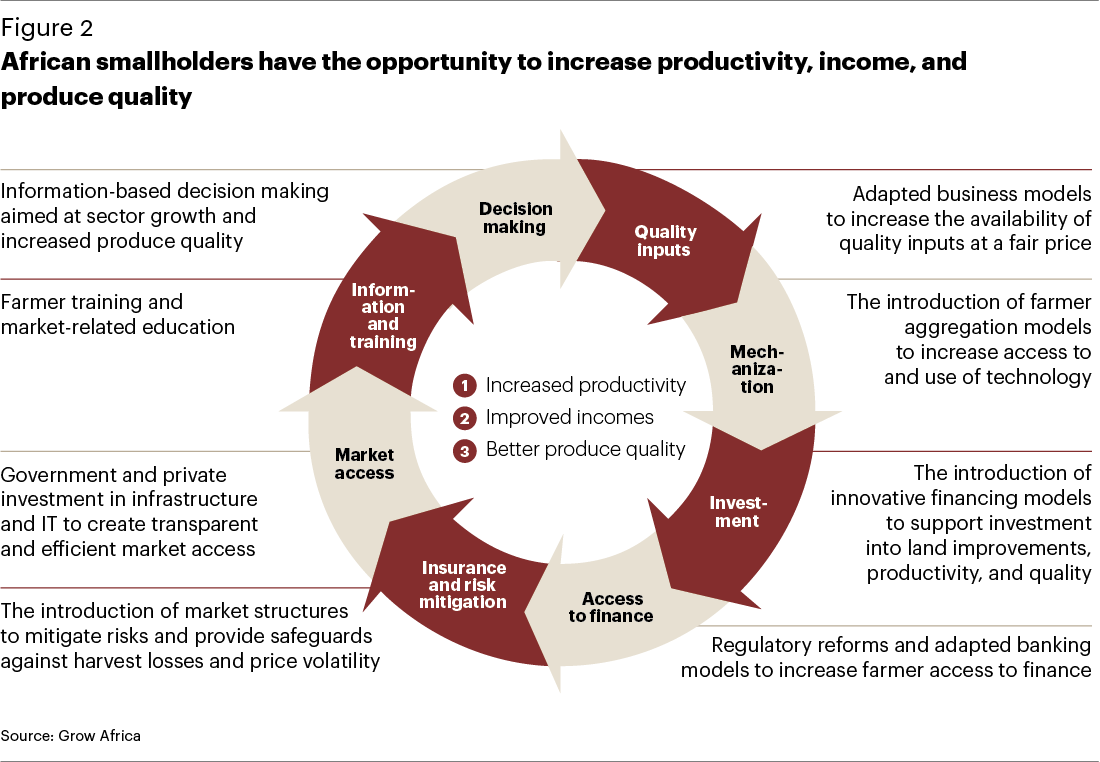

Financing will fund the improvements in the value chain on both the micro (farmer) and macro (export) levels. Government enablement means putting in place the regulations and structures that foster a strong business environment—for example, giving farmers title to the land they use, enabling them to use that land as collateral for loans for investments that can build. The development will become sustainably effective through the close interaction of public and private enterprises. Good governance is a prerequisite to ensure funds are applied in an effective and efficient manner. Farmer development leads to getting better products to the market. If markets are developed and allow for transparent pricing, the farmer gets a fair price and can become self-sufficient. As more farmers gain access to markets, it creates an ecosystem with enough resources to invest back into improved agricultural processes, which in turn improves yields and lowers losses. This will then facilitate clusters of best-in-class agricultural practices by crop and region that can succeed in the export market. All in all, it’s a self-propelling cycle that leads to advances and supports development of aggregation constructs (such as cooperatives), which help farmers jointly invest in productivity improvements and facilitate access to market (see figure 2).  Eight specific actions will optimize and grow the entire value chain. These are: Bring innovation to existing farm dynamics Improve access to markets Apply technology to increase market transparency Enhance farmer financing models Use targeted government enablement

Eight specific actions will optimize and grow the entire value chain. These are: Bring innovation to existing farm dynamics Improve access to markets Apply technology to increase market transparency Enhance farmer financing models Use targeted government enablement

Encourage sustainable agriculture practices Empower women Empower youth The following sections provide a brief overview of how Africa can move forward with these eight actions.Bring innovation to existing farm dynamics Smallholders have to understand a complex set of capabilities to bring the highest returns. These include mechanization (equipment for soil preparation, planting, cultivating, harvesting, and processing), irrigation, inputs (seeds, fertilizer, and the like), crop protection, product quality management, post-harvest protection (early processing, storage facilities, siloes, and warehouses), transportation, and direct access to market. The Gap Analysis Tool for Agriculture (GATA), developed jointly by Grow Africa and A.T. Kearney, provides farmer associations with a best-practice framework for smallholders, allowing for country- and crop-specific assessments of how they can improve productivity. The underlying objective of the GATA is to identify opportunities to increase farmer profitability and productivity by:

- Conducting a detailed analysis of value chains by region or country and by crop

- Enabling farmers, farmer groups, agricultural departments, and agencies to compare their practices against global and regional benchmarks

- Identifying agricultural value chain gaps and the investments required to close gaps

- Calculating the viability of smallholders closing these gaps

- Determining and providing visibility to decision makers and investors on which strategic interventions assure the highest benefits

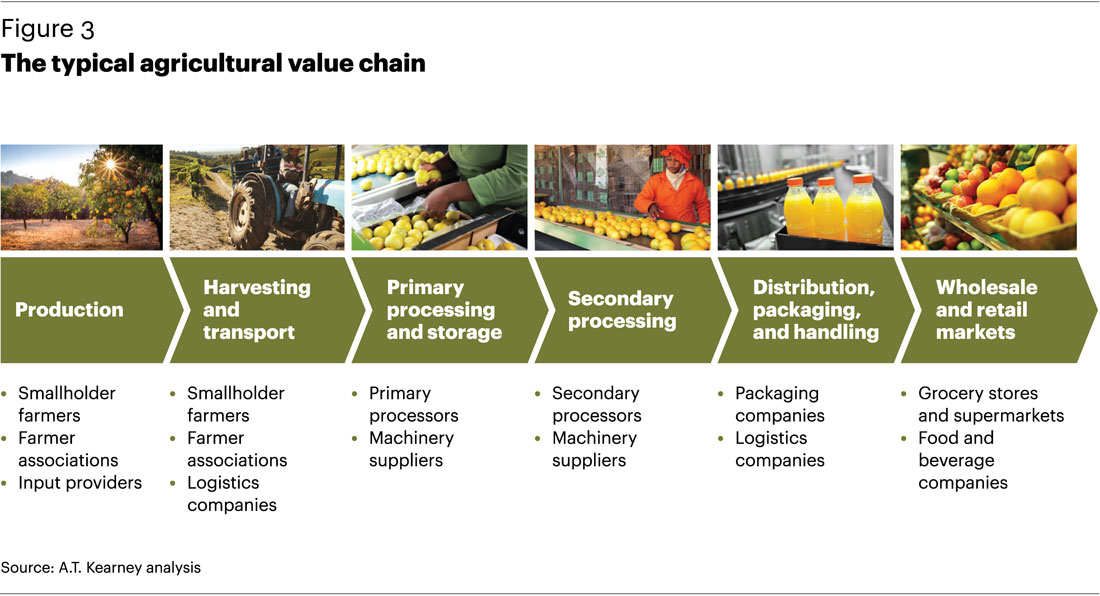

Improve access to marketsOne often-overlooked success factor is the structure of market incentives across the value chain from production to market (see figure 3). Unequal distribution of market power and insufficient access to the profit pool at various stages can have huge implications for farmers in low-income countries. Improving market access and transparency can balance market power, especially for smallholders.

Modern agricultural value chains have stringent requirements regarding volume, quality, and timely delivery. Combined with a lack of information on prices and selling opportunities and an abundance of “roadside traders” seeking high margins for low value added, smallholders generally find themselves with limited negotiating power and little incentive to grow beyond their current circumstances and to obtain their fair share of the profit in the value chain. Improving farmers’ information bases and introducing value-added market intermediaries are a prerequisite for farmer success. Many smallholders also lack physical and economic access to lucrative markets for their crops because they are physically isolated by distance, poor roads, and lack of access to adequate transport, and constrained by small crop quantities available for sale, inconsistent levels of quality, a need for immediate payment, and limited storage capacity. This highlights the need for public-private initiatives to build a physical supply chain (with storage, processing, and transport capabilities) that allows for quality products to be supplied to the markets in use. With unreliable information on production trends and prices and a lacking infrastructure, few smallholders engage in demand-driven or market-informed production, leading to inadequate production planning and cycles of production surpluses and deficits, which in turn lead to fuel price volatility. One solution to these problems comes from targeted government enablement, which gives smallholders greater market access and information

Apply technology to increase market transparency Ironically Africa has all the opportunity to jump the development curve and become a leader in applying technology to smallholder farming. The continent has high cell phone penetration and even in rural areas connectivity is good. Advanced cell phone applications (like banking, weather information, and market data) can help smallholders tremendously in their decision making and in improving their productivity. There are many examples of innovative uses of state-of-the-art technology that needs to be scaled across Africa (for example, small soil-testing devices that send data to a lab in Europe, which in turn provides soil-specific fertilizer advice by text message to the farmer). The interests for non-traditional private investors and African smallholder farmers go hand-in-hand. Africa provides a massive opportunity to test and commercialize data technology innovations and farmers are longing for the data that provides them with productivity and market opportunities. In specific, non-traditional agricultural sector players such as banks and telcos could step into this field and open new markets for themselves.

Enhance farmer financing models Affordable access to financing remains one of the most significant barriers to investment in agriculture. Access to financial services is critical for smallholders to invest in productivity, improve post-harvest practices, smooth household cash flow, enable better access to markets, and promote better risk management. In addition to formal financial institutions, input suppliers and product buyers often act as alternative financing channels for commercial and semi-commercial smallholders and cooperatives. Formal financing institutions are often hesitant to lend to commercial smallholders for a variety of reasons, primarily related to the scale of risks they face, including the heterogeneous nature of smallholder farmers, irregular cash flows caused by seasonality risks, systemic risk of flood, drought, and plant disease, and the lack of viable risk mitigation tools such as guarantees, asset collateral, and insurance. Financing institutions also struggle with loan processing and disbursement, customizing products for individual circumstances, and providing non-financial services, such as financial education, that will improve farmer success rates but are not core to the business. Farmers’ risks can vary widely. They are generally lower when farmers have stronger relationships with buyers, as this can bring techniques such as shared credit screening, monitoring, and collection, and the use of alternative collateral (such as sales contracts). When farmer-buyer relationships are weak, predatory lending becomes a bigger risk, and smallholders tend to be more focused on subsistence farming. Expanding lending to smallholders depends on several factors

Gaining detailed client knowledge at the smallholder level

Offering flexible loan terms that are adaptable to the diverse profiles of smallholders

Employing diversified risk management tactics, such as cooperatives and asset pooling

Training risk officers to better identify and manage smallholders’ risks

Re-engineering and adapting processes to ease applications and improve disbursement speed

Use targeted government enablement In addition to addressing smallholder needs directly, government can take steps to maximize returns on investment by creating an enabling environment for farmers in the following areas: land access, availability, and security; infrastructure; water management; education; labor; health and housing; security; investor environment; market structure; and public-private partnerships

The right enablers can have an outsized impact on agricultural outputs. This is exemplified by sustainable and equitable access to water.

Promoting techniques such as on-farm water management, rainwater harvesting, and conservation can potentially triple crop yields.

Improving rural water infrastructure can improve productivity, especially for women who spend hours a week collecting water for domestic and agricultural use.

Water capture and storage solutions can mitigate the impact of rainfall uncertainty.

Well-negotiated and managed private-sector presence in commercial agriculture can ensure fair access to water for smallholders.

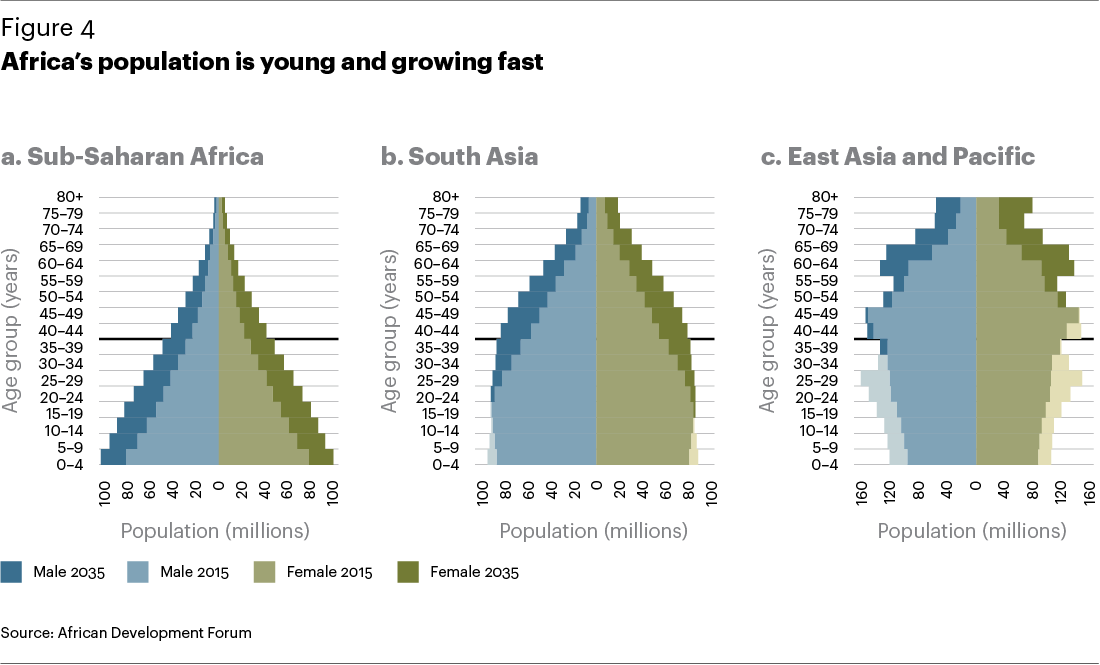

Empower women Many studies suggest that female empowerment can speed up development, as women reinvest their incomes in their families. For example, in Brazil, when income is a mother’s responsibility, a child’s survival probability increases by 20 percent; when the same happens in Kenya, a child is about 17 percent taller. If women worldwide had the same access as men to productive resources, yields could increase by 20 to 30 percent. The FAO estimates that gains in agricultural production alone could lift as many as 150 million people out of hunger. Most people today recognize the opportunity to close the gender equality gap; however, words of support only go so far. Recent work by the World Bank and the ONE campaign point to several barriers that women currently face in agriculture, including struggles finding adequate labor on their farms, unequal access to inputs, fair access to quality farmland, access to knowledge and training in farming methods, and a long-standing gender gap in education. Empower youth Sub-Saharan Africa’s population dynamics offer a unique opportunity, if managed well. Half of the population is younger than 25; every year between 2015 and 2035 there will be a half-million more 15-year-olds than the year before (see figure 4). This demographic dividend could radically accelerate Africa’s transformation if properly harnessed.

Over the next decade, however, as few as one in four Sub-Saharan African youth will find a wage job, and only a fraction of those jobs will be “formal” jobs in modern enterprises. Thus, agriculture will be central to providing meaningful and rewarding work. More than two-thirds of the young people who work in rural areas already work in agriculture, and most will remain there, even if the non-farm sector develops rapidly. As such, it will be important to help youth see farming not as an occupation of last resort, but rather one of opportunity and skill. Broadly speaking, agriculture offers three potential pathways for rural youth: full-time work on family farms; part-time farm work, combined with running a household enterprise (which can include the sale of farm services or inputs); and wage work. Several common constraints affect youth in agriculture: credit and financial services, land policies, infrastructure, and skills. Of these, only skills needs to specifically address youth at this point, as the others affect the wide pool of smallholders, regardless of age. In some countries, agricultural vocational institutes have traditionally provided these skills, but these institutes have mixed records of accomplishment; there is often a disconnect between academic teaching methods and the need for on-the-ground practical training. Well-thought-out extension programs and farmer-field schools have a bigger impact, especially if these are combined with support programs to entice youth to seek a living in farming

Encourage sustainable agriculture practices There are two simultaneous objectives here: improving the lives of Africans while minimizing environmental impact and ensuring that natural capital is not depleted. These objectives can be at odds with one another—in truth, agriculture is both a contributor to and victim of climate change—yet they can also be complementary. Sustainable farming, when done well, adds immediate value to the farmers as it increases the longevity of their operations and increases the value of their product

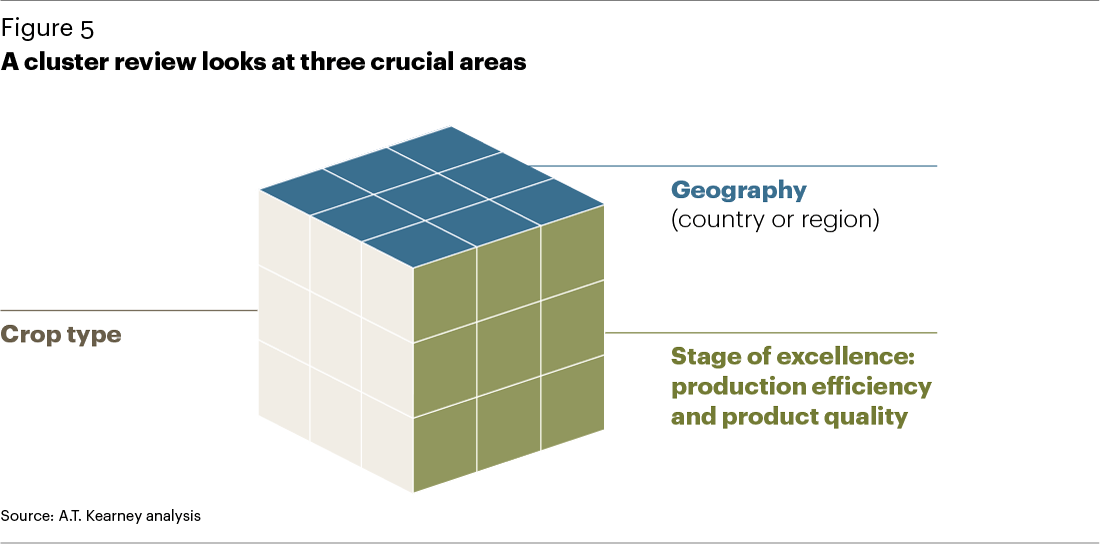

Cluster Development: Ensuring Viable Exports

With ecosystems in place, agriculture and agribusiness are huge economic opportunities for Africa, particularly if they can become revenue generators through an export model and enhance the continent’s balance of trade through value-adding operations. According to the World Bank, agriculture and agri-business will by 2030 be a $1 trillion industry in Sub-Saharan Africa, up from $313 billion in 2010. Agribusiness can help jump-start economic transformation through the development of agro-based industries that bring much-needed jobs and incomes. Successful agribusiness investments in turn stimulate agricultural growth through new export markets. These markets play either at the high-volume, low-value end of the market, or, ideally, they retain most of the value in Africa by incorporating value-added steps and local beneficiation in the value chain

The right clusters are driven by interactive, iterative, evidence-based analysis in which the main opportunities and constraints are identified through a combination of desk research, expert interviews, and workshops. In general, clusters with competitive advantage and already-proven investor demand are preferable over attempts to initiate new industries in new areas. Key policy reforms need to come before committing to large public investments. Priorities and action plans will need to be flexible enough to meet unanticipated cluster opportunities, yet also allow for constraints that will inevitably emerge. Finally, and crucially, strong governance and monitoring systems should be put in place to correct or terminate failures but most importantly replicate and scale up successes. It is time for Africa to grow!

Let’s Get Going

A few key numbers highlight the opportunity—and the challenge. To meet growing global food demand, production must increase by an estimated 50 percent by 2030. Sub-Saharan Africa’s 33 million smallholder farms—a number that will increase rapidly as the population continues to increase—contribute up to 80 percent of the region’s food supply. Improving the odds of prosperity for these farmers lies at the heart of prosperity for African agriculture. Success at the farmer, market, and cluster levels requires assistance from many sources.

Governmentsneed to focus on significantly improving the enabling environment for local agriculture, particularly as it comes to land rights, infrastructure, market access, and elevating women’s roles in society.

Pan-African institutions such as the African Union can help develop cluster opportunities across the continent and promote intra-Africa trade and best practice sharing.

The private sector can help invest with funds and knowhow, understanding that Africa’s potential for growth and its untapped arable land offer huge opportunities in spite of the risks. Public-private partnerships can unlock value, as long as both sides share the onus of success. No longer must Africa go hat-in-hand to feed its vibrant and resourceful population. It can help its own people feed themselves, their villages, towns, and countries. As scale and quality develop, export markets from the continent can flourish, leading increasingly to not just poverty alleviation but wealth creation. As more inhabitants see the promise of a better future in agriculture, many more clusters will be developed, truly making Africa the breadbasket that the world so desperately hungers for. It can be done. Now is the time to put our shoulders to the wheel.

Source: A.T. Kearney, 2015